1936. Heavy footsteps were running here and there in the royal house of the Sultan of Ramain. The five-year-old princess was dying. Her face was crimson red with escalating fever. Her eyes were half-open as if trying to take a last look at the world. Furthermore, her body was motionless and the faint beating of her heart was the only indication that she was still alive.

The whole family was trembling with clamped resentment towards the little girl’s aristocratic grandmother who was amazingly the only one who was calm, even proud and defiant. She ceremoniously tied her long black hair in the traditional pinalot and neatly fixed her malong as if preparing for the coming eventuality. Gently, she cradled the head of her granddaughter as if to ease her journey to the next world.

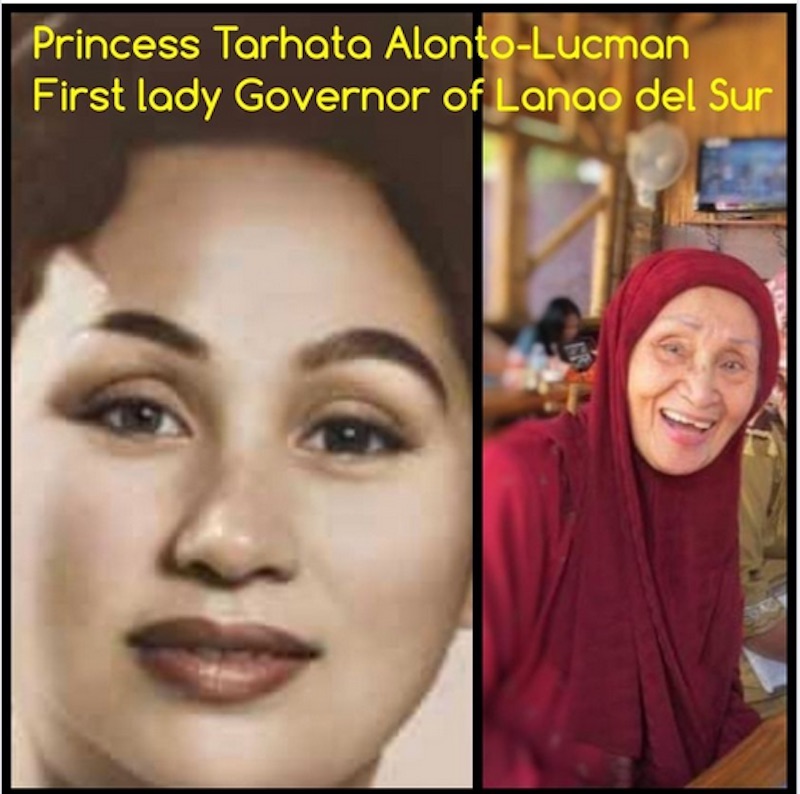

Princess Tarhata Alonto-Lucman, Philippines Free Press cover on 15 October 1949. Photo courtesy of the Princess’ family

Princess Tarhata Alonto-Lucman, Philippines Free Press cover on 15 October 1949. Photo courtesy of the Princess’ family

The little girl’s eyes flickered as if now ready to depart. The grandmother held the girl’s right hand and closed her eyes in silent prayer for the dying girl. The sudden breaking into uncontrollable sobs of the dying girl’s mother cut short the praying of the matriarch.

“Ina, please allow us to bring Tata to the hospital.” Fear for her daughter made her defy her mother for the first time.

“Nobody brings her to any infidel’s hospital. If she dies, then it is her time, but at least she dies a Muslim! My descendants are certainly not going to be the first to be Christianized!” She snapped back at her daughter while creasing her eyebrows in controlled fury. The grand old lady wasn’t going to let any saruang a taw touch the little princess. The princess is a Muslim, brought up a Muslim and she isn’t going to be Christianized in death, she thought.

An aleem was called upon to help persuade the iron-willed grandmother to let her granddaughter be treated in the hospital run by Christian doctors. Finally, she consented, after she was assured that there was nothing heretical in seeking treatment for the little girl.

The princess woke up a day later in a strange surrounding all in white. She was feeling intensely thirsty. She looked around and searched for familiar faces. There was none, only a stranger smiling at her speaking a language she could not comprehend.

“Paginoma sa ig.” The princess weakly commanded.

The nurse could not understand. She was a Christian and did not speak the language of the girl.

“Paginoma sa ig!” The princess was emphatic this time. Still, the attendant did not get water for her to drink, although she seemed to be trying to understand her. The princess thought hard. If she could not make this lady understand what she wanted, she would die of thirst.

“Tubig! Tubig!” The princess blurted triumphantly as she remembered the foreigner’s word for water.

“You’re thirsty! I am sorry, please wait.” The nurse hurriedly ran to get water, her eyes brimming with tears. The girl was brought to the hospital almost too late by her reluctant royal kin. Natives did not entrust their children to non-traditional healers. The little girl was the first patient ever among the proud Meranaws.

* * * * *

1972. The car screeched to a halt. Princess Tarhata Alonto Lucman, the first female governor of Lanao del Sur alighted. Unfazed, eyes alert, undeterred by the sound of raging gunfire she came in between the fire of two warring groups to stop the bloodshed.

It ended. It took a selfless princess to settle enmities of her people. Where there was rido, it was almost certain that she would surely come.

Settling feuds or rido’ of warring families had become normal to her. At times, she would come too close to danger but not even her husband’s concern for her, the Congressman Sultan Paramount of Bayang, Rashid Lucman could slacken her resolve to mediate between feuding families.

Princess Tarhata Alonto-Lucman, first female Governor of Lanao del Sur. From the FB page of Bai Annisa Alonto-Biruar

Princess Tarhata Alonto-Lucman, first female Governor of Lanao del Sur. From the FB page of Bai Annisa Alonto-Biruar

Her strong leadership wasn’t only felt in her province but throughout Mindanao. She became the chairperson of governors in Mindanao in 1972, a feat which wasn’t easy during the Martial law years for any opposition leader, and certainly not for a lady.

It was a challenge she easily and proudly tackled. She was not going to be intimidated by a dictator.

She always wore malong, symbolical of her deep attachment to her people and her culture despite breaking many barriers. While she was a trailblazer in fighting for equal opportunities for Moro women, she was indeed among the last few Meranaw women who still proudly wear their malongs everywhere. While at first she broke tradition, she also defied trends by opting to display her malong regally as only a princess could when penchant for non-traditional attire caught fire among Muslim women.

* * * * *

2004. Sixty-eight years after the hospital incident, the princess recalled how that event changed the course of her destiny and in effect the history of her people. When she was brought to the hospital, tradition was broken for the first time for her sake. But it wasn’t going to be the first, there were to follow many traditions which were to be broken by the princess. Her inability to communicate her need to the Christian nurse made her vow to learn the stranger’s language. At that time, rarely do Meranaws ever bring their children to be “Christianized” by going to school, definitely not the royalty too. But again, she broke tradition and went to school.

Her going to school was a breakthrough. She was the daughter of Sultan Alauya Alonto, the only Muslim senator in the Philippines and her going to school not only was a radical deviation from tradition but also paved the way for other Meranaw girls to follow suit.

An eager learner, she was accelerated three times in her first year in school. However, despite her desire to seek knowledge, tradition prevailed when she was in Grade 7. A very domineering uncle, Sheikh Besar, her father’s brother demanded that it was enough schooling for the girl, as she was now a lady. Sadly, this time, she wasn’t able to do anything, and she had to say goodbye to her dream of ever becoming a lawyer.

Princess Tarhata Alonto Lucman in 2004 during the Pagana Meranaw tendered by the Mindanao State University for Japanese guest Reiko Ogawa. To her left is the author. Photo courtesy of Elin Anisha Guro

Princess Tarhata Alonto Lucman in 2004 during the Pagana Meranaw tendered by the Mindanao State University for Japanese guest Reiko Ogawa. To her left is the author. Photo courtesy of Elin Anisha Guro

She considered her relentless pushing for reforestation during her incumbency and her benevolent yet strong-willed rule as some of her sterling achievements when she was the governor. However, to the many Meranaws, it was her paving the way for the education and leadership of women which is the most memorable and significant achievement she had ever done. Her determination to go to school opened the gates of education for women. While she wasn’t able to finish her studies, the growing number of educated Meranaw women was enough consolation to her. Her becoming a governor served as an inspiration to Meranaw women.

Indeed, not everybody is like the Princess who refused to receive her salary as governor but divided it instead to her employees. Not everybody is like her, whom everybody calls a Princess, yet refused and did not want to be called a princess. Little did her grandmother know that the granddaughter who almost died because of her would also become a matriarch like her, not only of her family but of her people. While they both share an unflagging determination, the little girl was to become the grand matriarch of all.

After many decades, people still remember her as the Princess, but to her many relatives and those who know her closely, she is called Babo a Tatah— a name, a title, a pet name only for her. The Meranaw woman has now come a long way. Babo a Tatah, as she is known to her people, led the way.

Note: Princess Tarhata Alonto Lucman passed away today, February 26, 2021 in Marawi City. I wrote this in 2004 based on my conversations with Ina a Tatah. At that time, Ina a Tatah was my special guest in a program for Moro women I was working on. I would often visit her at her residence, Langagen in Marawi City. She would also pay me a visit at home and it was during these visits that she would share snippets of her life with me. I fondly call her Ina a Tatah, short for Ina a Ba-i as do many of her cousins’ grandchildren because she is a cousin to both my maternal and paternal grandparents. Today, I fondly recall those precious moments I spent with her and this is my tribute to her. Rest in Peace, Ina. Your legacy shall live on.