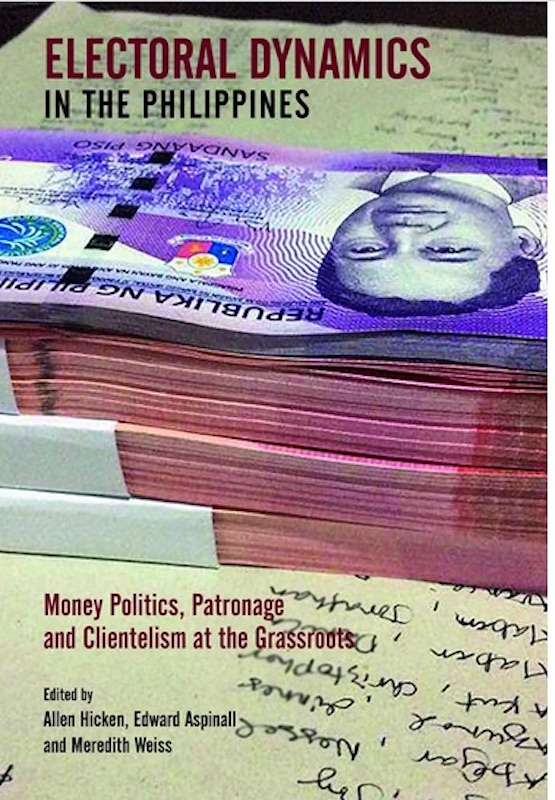

Book Review: Hicken, Allen, Edward Aspinall, and Meredith Weiss, eds. Electoral Dynamics in the Philippines: Money Politics, Patronage, and Clientelism at the Grassroots. Singapore: NUS Press, 2019.

WASHINGTON, DC (MindaNews / 06 September) — While residing in Singapore during the 2016 Philippine election, my only brief glimpse into the local campaign came during a visit for a fieldwork. As most balikbayans can attest, a two-week trip is never enough, but this time it was way more than fascinating as an absentee voter. This is even more pronounced as my hometown, Davao, saw its mayor on the national political stage campaigning for the Presidency.

Seen as a relative latecomer in the race, Rodrigo Duterte relied heavily on his tightly knit local political machinery. This is not unusual as revealed in the book Electoral Dynamics in the Philippines: Money Politics, Patronage, and Clientelism at the Grassroots. The volume casts light on two salient factors that characterize electoral mobilization in Philippines politics – (a) the nature of political alliances and machines; and (b) the role of money in lubricating the wheels of those machines and mobilizing voters.

In basic terms, patronage is a tangible resource that politicians provide to voters, campaign workers, and contributors, in exchange for their political support. Patronage can materialize in the form of cash being distributed to voters (labelled “allowances” in Pampanga, uwan-uwan in Bohol, “banquet” or salo-salos in parts of Laguna) that run from PhP20 to Php1000 on up to even several thousand pesos. Apart from money, candidates also give out a mix of individual items such as t-shirts, fans, scholarships, sports jerseys to even collective goods delivered to bastions of support such as infrastructure projects. While patronage focuses on material benefit delivered, clientelism characterizes personal relationships that bring critical mutual benefit, notwithstanding ever-shifting political alliances in the Philippines.

In basic terms, patronage is a tangible resource that politicians provide to voters, campaign workers, and contributors, in exchange for their political support. Patronage can materialize in the form of cash being distributed to voters (labelled “allowances” in Pampanga, uwan-uwan in Bohol, “banquet” or salo-salos in parts of Laguna) that run from PhP20 to Php1000 on up to even several thousand pesos. Apart from money, candidates also give out a mix of individual items such as t-shirts, fans, scholarships, sports jerseys to even collective goods delivered to bastions of support such as infrastructure projects. While patronage focuses on material benefit delivered, clientelism characterizes personal relationships that bring critical mutual benefit, notwithstanding ever-shifting political alliances in the Philippines.

This volume is composed of works from several researchers in the Philippines who were invited to detail their observations and investigate how campaigns are managed and conducted locally. For weeks, they interviewed candidates, campaign staff, and vote brokers (termed local liders); shadowed campaign sorties; observed campaign events; and scrutinized both the messages and gifts that candidates and their teams distributed. The result is a collection of 15 ground-level case studies across the country centered on candidate strategies, their organizations and networks, and ultimately voter behavior.

The role of money and patronage materializes in many forms across the Philippines during national and local political contests. This book seeks to dig deeper to examine the networks and dynamics of the patronage system, to build a more comprehensive picture. Some of the contributors focused on a single city or province, while others looked more narrowly at a single congressional constituency, or even just part of a constituency.

A typical downside to this approach is the perspectives of these chapters becomes repetitive. While readers gain perspective from these deeper dives into specific cases, there is a chance they may not derive the broader trends after reading this book.

It is abundantly clear that deviation from the norm of patronage and clientelism is uncommon. Most of the candidates rely on money to engage with their constituents (and hopefully win). Conversely, local liders gravitate to the party (or individual) with most resources, as these relationships are held together by expectations of reciprocity. Albeit, the chapters also describe interesting and important themes that vary from this broad trend. In Chapter 10, Mary Joyce Borromeo-Bulao illustrates how Naga City institutionalized the distribution of government services through coordination and consultation with grassroots organizations. In Chapter 13, Regina Macalandag examined the issue of gender in patronage politics in Bohol.

The editors argue that at the core of Philippines patronage system are local political machines, established around a local politician or family/clan, that operates both upward to the national-level politicians and parties, as well as down to the lower-level politicians and local voters. This is not surprising as national political parties in the Philippines are generally weak and Filipino candidates are known to shift alliances. However, solely relying on these local party machines does not automatically translate into electoral success for candidates. This volume notes that this also requires financial backing, in many cases popularity (e.g. name recall), and in some, varying degrees of coercion. Acram Latiph describes this as the 4Gs (gold, goons, guns, and genealogy) as is the case of Lanao del Sur in Chapter 17.

This book is a welcome addition to the scholarship on politics and governance, detailing a distinct modal pattern of resilient local political machines in contemporary Philippine electoral politics. Even with just a focus on a single national-local electoral cycle, this volume reflected an ambitious research agenda and the efforts of the authors and researchers is to be commended. Similarly, the editors noted that the individual case studies do not focus on the source of patronage resources, but rather on the disbursement process carried out during each case. This would be a good topic for a follow-on project.

(MindaViews is the opinion section of MindaNews. Ava Patricia Avila is a Strategic Fellow at Verve Research, an independent research collective focused on the relationship between militaries and societies in Southeast Asia. She holds a PhD in Defense and Security from Cranfield University. Born and raised in Davao City, with experience working on gender and development issues across Mindanao, she currently resides in Washington, DC)