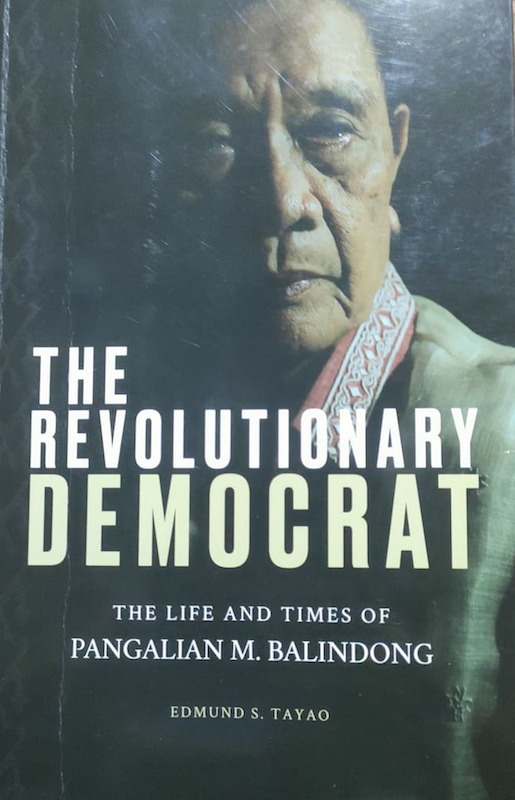

Book: Revolutionary Democrat: The Life and Times of Pangalian M. Balindong

Author: Prof. Edmundo S. Tayao

Published in 2021 by JNPM Graphic Design and Printing Services, Mandaluyong City

COTABATO CITY (MindaNews / 29 August) — Speaker Ali Pangalian Marohom Balindong of the Bangsamoro Transition Authority delightfully shares that efforts by representatives of Muslims and Indigenous Peopless in Congress bore more fruits with the enactment of House Bill 4832 he once initiated, now Republic Act 10908, the “Integrated History Act of 2016.”

The law mandates the integration of Moro and Indigenous Peoples’ History, Culture, and Identity in Studies of Philippine History. To be fair, Jesuit chroniclers (Spanish Regime) and American historians (Moroland) most probably had factual records of many crucial parts of Moro history. The Jesuits’ materials have been interpreted by scholars like Dr. Nejeeb M. Saleeby, Dr. Cesar Adib Majul and Atty. Datu Michael O. Mastura, among others, for their own works. The problem is that neither the old materials nor the scholars’ works have been reduced to the language of the classroom — unlike the works of Gregorio Zaide, Julio Nakpil, Milagros C. Guerrero, and others on historical accounts from the north

The law mandates the integration of Moro and Indigenous Peoples’ History, Culture, and Identity in Studies of Philippine History. To be fair, Jesuit chroniclers (Spanish Regime) and American historians (Moroland) most probably had factual records of many crucial parts of Moro history. The Jesuits’ materials have been interpreted by scholars like Dr. Nejeeb M. Saleeby, Dr. Cesar Adib Majul and Atty. Datu Michael O. Mastura, among others, for their own works. The problem is that neither the old materials nor the scholars’ works have been reduced to the language of the classroom — unlike the works of Gregorio Zaide, Julio Nakpil, Milagros C. Guerrero, and others on historical accounts from the north

One sees a deep sense of independence in the man’s speeches, deeds and views expressive of his character by which he holds principled stand on issues concerning the welfare of his people and the community.

As a young professional, he broadly studied the Islam faith that he firmly holds in all his diverse engagements living and working with and among followers of other religions.

The sense of struggle to be at par and be fair with the majority is best exuded in his early life experience as a student faring well with his schoolmates in pre-law and in College of Law in Manila’s famed Manuel L. Quezon University, when the population of Filipino Muslims in the then Greater Manila Area was too small.

Relevantly, the infamous Jabidah Massacre took place on March 16, 1968, just a month after the results of the bar examination the previous year was released in February 1968.

The incident would stimulate activism, mass protests, even armed revolt starting with his generation of Moro students, and — for his part — awareness and articulation of how this would hurt if not defeat a key pre- and post-war essential state policy: the integration of the minority into the mainstream society.

“Fast-changing world”

These and facing the challenges amid a “fast-changing world” sets the potentials that emerging young leaders are made of — as readers will learn from the book “The Revolutionary Democrat: The Life and Times of Pangalian M. Balindong” by Professor Edmundo S. Tayao.

Balindong comes from an illustrious clan of leaders and politicians, starting with his father Sultan Amer Macaorao Balindong, a mayor of Malabang, Lanao del Sur for decades. Amatunding, the ancestor of his forebear Nago sa Picong, was married to Potri Gayang, sister of the 17th Century Muslim Hero Sultan Muhammad Dipatuan Kudarat, a historical figure in the chronicles of Jesuit Francisco Combes, and as written by great Filipino historians like Dr. Cesar Adib Majul.

Political attempts to replace Mayor Sultan Amer Balindong by Marcos allies during martial law led to gerrymandering by which his town had been subdivided into four municipalities with Balabagan, Sultan Gumander (later renamed Picong), and Kapatagan partitioned from Malabang’s original land area. Two of these municipalities have been under the administration of the Balindong siblings, succeeding their old man.

Lanao del Sur’s second congressional district to which these municipalities geographically belong, is represented in Congress by his son, Yasser.

Sultan Balindong had covertly hosted in the hills and riverbanks of Ramitan village in Picong the First Batch of 90 Moros, also known as the “Top 90” who trained on military combat and administration of casualties in Pulao Pankur Island Kedah in Malaysia in 1969. Then already a lawyer, Pangalian Balindong recalls fetching the trainees in small boatloads from Bongo Island in Parang, Maguindanao to Ramitan seashore village in Picong.

Chief Justice Raynato S. Puno (Ret), who wrote the first Foreword of “The Revolutionary Democrat” says the real measure of independence of the 2018 Constitutional Commission formed by President Rodrigo Duterte to review the 1987 Constitution, was on how it voted on the provision of political dynasty.

“The entire nation was watching us for it was the litmus test of our independence from well-entrenched politicians in control of the levers of power in government,” CJ Puno wrote, describing the 2018 ConCom deliberation and vote on the constitutional ban on political dynasty.

Banning political dynasties

“But what brought the house down was the speech of Speaker Balindong, Puno adds, quoting his colleague in part saying: “I come from Lanao del Sur, the capital of political dynasties in the Philippines. I myself belong to a political dynasty.”

Puno, in sheer reverence of his colleague from Lanao del Sur, noted: “And then he (Balindong) explained in unadorned language that he was voting against his self-interest, hence, he favored the ban (on) political dynasties.”

Professor Tayao walks us through world state of affairs — during which Balindong would lead early life, as a college student and as professiona l— such as post-World War II developments, the Cold War, the emergence of new nations, and domestically later, the changing socio-political landscape from state policies on integration to growing sentiments for Moro secessionism in Muslim Mindanao.

All these, Prof. Tayao points out, helped the young Balindong prepare for greater challenges and make important decisions on his track to professional life as a lawyer and as an emerging leader to his people.

The young Balindong was a classroom student of noted nationalist Sen. Lorenzo M. Tanada when he was in MLQU School of Law in Manila. It was in his after-class frequent pastime sitting in the galleries of the Old Congress, along Orosa St.-Taft Avenue, that he saw and probably learned early his parliamentary skills from some of the legislative giants of Philippine history — Senator Claro M. Recto, and later, Senators Jovito R. Salonga and Jose W. Diokno, among others.

But Prof. Tayao barely relates these facts of Balindong’s early life to a situation obtaining back home that timely connects his learning of law and experience in and out of the classroom: the labor and agrarian issues in Malabang and its community implications in relation probably to Tanada’s known pro-labor advocacy both as a senator and a law school mentor. Senate floor deliberations involving the grand old man, along with Recto, and in later Congress, Salonga and Diokno, taught him actual lessons as to how they firmly held principled position on issues, probably more than developing parliamentary skills he acquired over time.

Plantations and resistance

Malabang, the hometown of the Balindongs, has been a host to industrial plantations, notably, the 5,000 hectare Matling Industries owned by the Spencers, an American couple, as well as the vast coconut plantations in Balabagan, an old agricultural colony, which used to be part of Malabang. The Spencer couple came in 1914, shortly after the creation of the Department of Mindanao and Sulu by the American Administration of Moroland.

Speaker Balindong describes the relationship between his old man and Mr. Spencer: “They never saw eye-to-eye in their lifetime.”

Malabang’s population is made up of diverse tribes with various religious affiliations that have been well led by the Balindongs.

The relation between the local government unit of Malabang and the industrial plantations was severed by the day, and even came to a point that the Mayor Sultan Balindong would ostensibly ban recruitment of his constituents, be they Muslims or Christians, to work as laborers of these vast plantations — lest they experience labor grievances and their voices would not be heard from walled corporate territories.

During martial law, the Matling plantation had to make its labor package “attractive” to Maguindanao Moro workers seeking employment by resettlement on intercession of some cooperating datus. (Currently, there is a massive retrenchment that leads to displacement of old Maguindanaon working families inside the plantation, now under a succeeding Filipino management).

To paraphrase Joshua Karliner, author of the book “Corporate Planet” Speaker Balindong says, “It (the industrial plantation) is there, like a state within a state. It has its own everything, including water and power lines. It is well-protected by our state security forces (from any labor unrest that may arise and gain support from some external force of interest).”

Execution of a Chief Justice

Chief Justice Jose Abad Santos, who was designated acting President by exiled President Manuel L. Quezon, was taken to Parang, Cotabato (now Maguindanao), along with his son, his namesake, from San Nicolas, Cebu, after his arrest there. Like Dr. Jose Rizal to the Spaniards, it was probably Abad Santos’ choice to be brought to “exile” in Mindanao for some “sanctuary” which his captors granted perchance he might reconsider his decision against signing a commitment to cooperate with the government set up by the invading foreign forces. For otherwise his captors could have just carried out his execution covertly anywhere in Cebu.

One such probable “sanctuary” was a coconut plantation in Bugasan, Parang, Cotabato (where he was initially brought to). The American plantation owner had apparently escaped the invasion persecution — and later sold the estate to a native Iranun trustee, Hadji Datu Usman Mampen. The second potential place of “exile” was the Matling Plantation run by the American Spencer couple in Malabang to which he was brought next (apparently in hope that he would at the “last-minute” change his position against cooperating with the Japan-sponsored Philippine administration once in exile). Indeed, many of the POWs (prisoners of war) who had lain low during the war were brought to Malaybalay, Bukidnon (including Manuel Roxas) and were liberated from there by a combined strength of Christian-Muslim Guerrillas of the Cotabato-Bukidnon Force under Col. Salipada Pendatun (Col Uldarico Baclagon in Moslem-Christian Guerrillas of Mindanao)

Then Defense Secretary Fidel V. Ramos acknowledged the military triumphs of the mixed Muslim and Christian guerrillas fighting as one force “against a common enemy” in his foreword of Col Baclagon’s book. And such was the essence of Balindong’s articulation he particularly expressed in his first privilege speech at the Constitutional Convention of 1971— that the Muslims needed “no further proof to show that they can love this country as much as their Christian brothers do.”

Education, early years in politics

Balindong was born on January 1, 1940 in Tanaon, Dapao Pualas, Lanao del Sur to Sultan Amer Macaorao Balindong, former mayor of the Municipality of Malabang, Lanao del Sur, and Hajjatu Maimona Marohom Balindong

He completed his primary education at the Malabang Central Elementary School in 1954 and finished his secondary education at the Our Lady of Peace High School in 1958. He earned a degree in political science at the Manuel L. Quezon University in 1962 and obtained a Bachelor of Laws degree in 1966 at the same university. He passed the Philippine Bar Examination in the following year. He has earned units leading to a degree in Master in Public Administration at the Mindanao State University. He is a member of the Mu Kappa Phi Law Fraternity.

Balindong was elected Delegate to the Philippines Constitutional Convention of 1971, representing the lone district of Lanao del Sur.

On the sidelights, Balindong was in charge of English literature in a team formed by his father in-law, the late Senator Ahmad Domocao Alonto that endeavored to translate into the Maranao Dialect the Revelation Language of the Holy Qur’an. He was particularly assigned to a task of interpreting in his mother tongue the literary lines of the English Translation by English Muslim scholar Muhammad Marmaduke Pickthall.

Two months after he passed the bar exam, Pangalian married Hajjatu Jamela Malawani Alonto on April 28, 1968 with whom he is blessed with eight children, 24 grandchildren and two great grandchildren as of the writing of the book.

The voluntary works and his membership with the Ansar el-Islam (The Helpers of Islam) also founded by Senator Alonto took him to an important Philippine delegation to the International Muslim Youth Conference in Tripoli, Libya in 1973 on the convention subjects that pertained to Palestine, the Southern Philippines and Southern Thailand.

International exposure

Balindong’s international exposure along the issue of the minority’s right to self-determination afforded him the occasion to articulate issues and events affecting the Moro people in Mindanao — a move he had amplified with his first Privilege Speech at the Constitutional Convention:

“We have, in recent months, seen an emerging pattern of persecution directed against the Muslims, particularly, in the province of North Cotabato (referring to the June 19, 1971 Manili Massacre in Carmen), Lanao del Norte and Lanao del Sur.

“Rightly or wrongly, the Muslim Filipinos are beginning to feel that they are being isolated from the greater mass of the Christian brothers as if they were lesser Filipinos than the latter. The events of the recent past which saw the mass killings of innocent men, and women and children inside religious sanctuaries, their shooting in cold-blooded of unwary Muslim voters, and wholesale burning of Muslim homes, the pillage and plunder of the farms, cannot but be interpreted as part of a preconceived plan to constrict and restrict Muslim freedom when we consider that to date, not a single malefactor has been brought before the bar of justice to account for this ghastly, and dastardly acts. Unless something is done by the government, nay this Convention, to stern the rising tide of hostility and antagonism between the Christian majority and the Muslim minority in this country, the conflict is bound to create bigger problems which may eventually lead to disintegration instead of integration.”

But even in those situations of imminent risks of bigger conflict from apparent biases, even bloody instances of religious persecution, you can fairly listen to the man and feel how he drives you back to the course of “Unity in Diversity,” the very title of his Privilege Speech:

“This is probably the reason why, during the few days that I have been in this Convention, I had the occasion to find among the resolutions filed with the Body, a couple of them urging the incorporation into the proposed constitution of provisions especially designed for the minorities. This, indeed, is a healthy sign which inspires hopes among the Muslims of this country that, at long last, they shall find their rightful place in this land they so fervently love and venerate.

“It is exhilarating to note that these Resolutions having to do with the protection or enforcement of the rights of the religious and ethnic minorities of their country have been co-authored by Delegates form all segments of our people.”

According to sources from among his fellow ConCon (Constitutional Convention) delegates, Balindong declined to make official his first travel to Tripoli, Libya towards the end of the Convention in 1973, because he was invited as representative of the Moro youth and not as member of the 1971 ConCon.

Right to self-determination

The travel would prove significant to the Moro people’s struggle to self-determination as this led to continuing dialogue and articulation overseas (to oil-rich Arab Muslims) of the plight of the Moro people back home.

At the international youth conference in Tripoli, Libya in 1973, Balindong met fellow Moro lawyer Zacaria Candao, as legal counsel for the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF), and Salamat Hashim as foreign minister and vice-chairman of the Moro revolutionary movement. Prior to this, Hashim had sent off in Zamboanga City the second batch of 300 Moro men for a military training at a Malaysian territory as facilitated in February 1971 by Dr. Muhammad Salih Loong.

“Interestingly, the future of the Philippines was laying on the future of Asia, especially the Southeast Asia Region. It was pivotal time as it was turbulent. It was also a time filled with promise for everyone and the country as a whole,” wrote Tayao.

Tayao noted: “The leaders of the country, and even that of the Bangsamoro, had to be careful and, more importantly, crafty. They had to navigate the recondite, formidable and complex hierarchical international politics. It was an environment that any leader would be inclined to think, more than anything else, that everything that had to be done would be for the good of the country and the people.”

Indeed, Balindong, Hashim and Candao had it right that amid oil crisis from the 1973 OPEC (Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries) oil embargo with the heightening tension in October 1973 from the Arab-Israeli War (Yom Kippur War), the strategic and pivotal point was in Libya. With Libya as refuge, the Marcos government would be compelled to go into bargaining at the negotiation table. Otherwise, Marcos could have negotiated with China or even Russia for oil import amid worsening oil crisis triggered by the 1973 embargo. But Marcos also knew that Libya, being a socialist people’s Arab Jamahiriya republic, could influence other socialist people’s republics against any oil deal with the Philippines, pending resolution of the conflict in Mindanao.

Negotiating peace

In the July 1975 Meeting of the Organization of Islamic Conference (now Cooperation) in Jeddah, Marcos sent a government delegation for the Southern Philippines composed of Governor Simeon A. Datumanong, Rear Admiral Romulo Espaldon, Ambassador Lininding Pangandaman, General Mamarinta Lao, and Elections Commissioner Ameen Kadri Abubakar.

True enough, in October 1976, Libyan leader Col Muamar Qaddafy agreed to meet Imelda Romualdez-Marcos who was then accompanied by Datumanong, Pangandaman, Deputy Foreign Minister Manuel Collantes, Ambassador Pacifico Castro, Colonel Fabian Ver, Espaldon, and General Fortunato Abat. This meeting was followed by a series of trilateral dialogues and negotiation between the parties of the Philippine government and of the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF), and top ministers of the hosting OIC – notably, Libya’s Minister of State for Foreign Affairs Dr. Ali Abdusasalam Treki, with the participation of the Quadripartite Ministerial Commission and the aid of Dr. Amadou Karim Gaye, Secretary-General of the OIC.

The MNLF Panel was composed of Nur Misuari, Abdulbaqui Abubakar, Salamat Hashim (who hardly sat in the panel), Abdurasad Asani, and with Atty. Zacaria A. Candao and Atty. Pangalian Balindong as members of the MNLF Legal Consultative Panel.

The Government Panel was led by Defense Undersecretary Carmelo Barbero, with Collantes, Castro, Abubakar, Pangandaman and Datumanong, as members. The first Peace Agreement was signed in Tripoli, Libya on December 23, 1976. The pact came to be known as the Tripoli Agreement of 1976.

After the Marcos overthrow by military-backed civilian uprising in February 1986, succeeding President Corazon C. Aquino officially reopened the Peace Negotiation with the MNLF when she, along with Defense Secretary Juan Ponce Enrile and AFP Chief of Staff General Fidel Ramos, met Misuari and company in Jolo, Sulu in 1986.

Following the ratification of the 1987 Constitution and the congressional elections that year, the first post-martial law Congress enacted Republic Act 6734 which created the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (ARMM) upon the ratification of that law in November 1989.

ARMM Governors

Candao ran for ARMM regional governor and won over Lanao del Sur Gov. Muhammad Ali Dimaporo in February 1990. Balindong ran and won a seat, representing the second district of Lanao del Sur in the ARMM Regional Legislative Assembly (RLA) in Cotabato City which he served from 1993 to 1995. He was elected congressman of the same Lanao del Sur district in the Tenth Philippine Congress, succeeding Sultan Muhammad Ali Dimaporo.

As ARMM Assemblyman, he chaired various RLA committees, including the Committee on Education, Culture and Sports; Committee on Public Order and Security; and Committee on Agriculture and Food.

He sponsored and authored the ARMM law prescribing the registration of births, deaths and marriages in the region; the law establishing the Bureau of Agriculture and Fishery, and the creation the Lanao Lake Integrated Development Authority, as well as the regional law creating of the Bureau of Cultural Heritage.

He also served prominent roles in the RLA including his elective terms Majority Floor Leader and Speaker. He was also a member of the Regional Executive Development Council and Regional Peace and Order Council of ARMM.

Balindong worked primarily on the age-old quest for self-determination of the Moro people in Muslim Mindanao. In his commitment to just and lasting peace, he introduced and co-authored the Bangsamoro Basic Law (BBL) – although efforts to push for its passage did not succeed in the 16thCongress. (We note that in the book, the BBL appears like it was passed albeit renamed Bangsamoro Organic Law (BOL) in the same Congress. The BOL however, was passed by the 17th Congress, in July 2018.

Mothers singing lullabies

But it is worthy to note that in his sponsorship speech for the BBL in the House of Representatives in 2015, Balindong shared his vision for the Bangsamoro people “where all fathers in full dignity, can provide for their families, and mothers can sing lullabies to the babies not amidst gunshots, but amidst the peace and serenity of Nature, and children can live their childhood as childhood should be lived – in gleeful play, in earnest study, and in nurturing embrace of family and community.”

Tayao wrote: “It is Balindong’s dreams to have a developed and proud Bangsamoro.”

In his sponsorship speech, Balindong said: “I dream of an enlightened Philippines. I dream of an enlightened national, regional and local government working together, not one second-guessing and imposing on others. We are now at the troughs of making this dream a reality. Together, I am confident we shall get through it, proud and triumphant.”

Another vital legislative initiative that Balindong sponsored is the Commission on Muslim Filipinos Act of 2009 (RA 9997) which created the National Commission on Muslim Filipinos (NCMF), mandated to preserve and develop the culture, tradition, and well-being of Muslim Filipinos in conformity with the country’s laws and in consonance with unity and development.

Balindong also initiated House Bill 4832 which has been enacted into law as RA 10908 also known as “Integrated History Act of 2016” which mandates the integration of Filipino Muslims and Indigenous Peoples’ History, Culture, and Identity Studies in Philippine History. He also lobbied for House Bill 1447, which prohibits the use of the words “Muslim” or “Christian” in the mass media to describe any person suspected of or convicted for committing criminal or unlawful action. He argued if the media puts labels on suspects and convicted criminals regarding their nationality, ethnicity, and religious affiliation, it connotes negative impression on people same religious or ethnic affiliation.

In 2018, he was appointed as member of the Consultative Committee to Review the 1987 Philippine Constitution (ConCom 2018) by President Rodrigo R. Duterte. He chaired the Sub-Committee on the Bangsamoro.

Nash B. Maulana is a Peace Journalism research fellow of the Konrad Adenauer Stiftung and the Philippine Center for Islam and Democracy (2010). He has authored two documentary books: Kadtabanga: The Struggle Continues (2005),[1] and Empowering Communities: The ARMM Experience (2014).[2] His other scholarship programs include the Reporting Tour of the East Coast, a grant by the Foreign Press Center, the U.S. Department of State (2011), and the Peace Journalism Training Program by the Center for the Studies of Peace and Conflict, University of Sydney.

As a journalist, Maulana has written articles for the Philippine Daily Inquirer, the Philippine Free Press, and The Mindanao Cross., where he has a weekly column. He is presently a news contributor of the Manila Standard. He finished BA Journalism at the Polytechnic University of the Philippines.