MATI CITY, Davao Oriental (MindaNews / 28 February)—Indigenous peoples (IPs) have existed and taken care of the environment long before I even had the mental agency to articulate my thoughts into words. Unfortunately, they are often left out of discourses regarding their communities.

In the Philippines, a country dubbed as one of the most dangerous places for environmental defenders, many narratives perpetuated by media surrounding IPs are often anchored on their struggles. While this may not entirely be a wrong practice, it becomes myopic when they are reduced to mere portraits of poverty who need saving.

Moreover, there is abundant coverage of climate change impacts or displacement from ancestral domains, but rarely do we consume media that are solutions-based and dig deep into the social, historical, and cultural underpinnings of these issues.

We’ve heard news about indigenous activists being jailed, Lumad teachers being red-tagged, or fishing communities being ravaged by mining operations. In many instances, this type of reporting explicates the cause of a problem and ends with the presentation of its evident effects.

But what about what happens after?

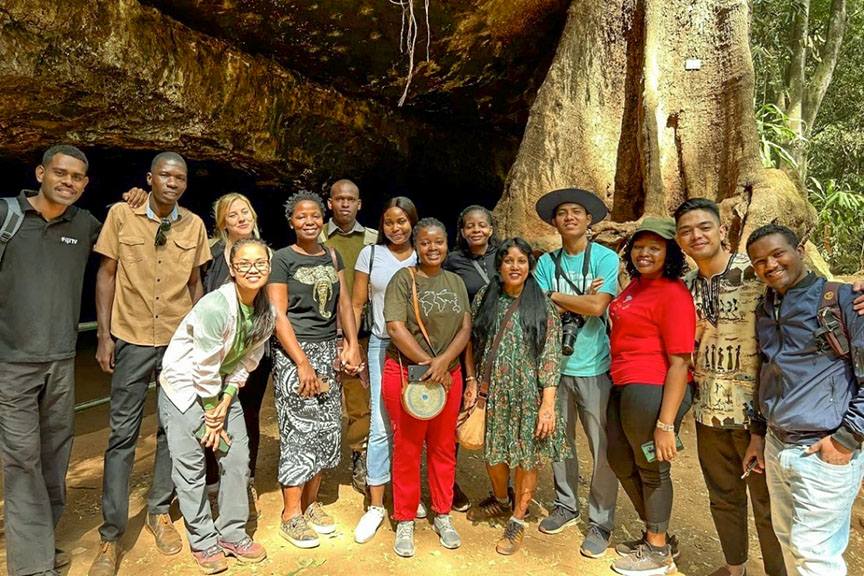

This question was among the many discussions that were central to my three-day training last February 21-23, 2023, in Nairobi, Kenya. The event gathered 10 journalists from around the world to learn more about effective and ethical indigenous environmental reporting.

Indigenizing environmental journalism

In her talk on indigenous journalism, Zeynab Wandati, an award-winning science journalist, underscored the power of media in presenting underreported environmental stories surrounding IPs. When disasters happen, we are quick to label them as a natural occurrence without trying to understand the human intervention that could have exacerbated the phenomenon.

For Wandati, we should broaden our analysis on these matters, and ask ourselves questions like: “Is it exclusively a natural disaster or is it man-made?” She highlighted that as journalists, we must always be critical in our reportage.

This example made me think about COVID-19 which disproportionately impacted marginalized communities at an unprecedented rate. Many claimed that the pandemic caused hospital infrastructures around the globe to fail. But was this solely because of the coronavirus or did it merely expose the fragile healthcare systems that were already on the brink of collapse from the very beginning?

A trip to the “lungs” of Nairobi

While I was lining up at the airport, an immigration officer, upon seeing my documents, raised an eyebrow and asked, “Why here, of all places?” At that point, I found it difficult to respond to his question. What can I say about Kenya? Why did the event have to be in this country?

I got my answers in a forest.

On the second day of our training, we had a field trip to the Karura Forest, an upland urban forest dubbed as the “lungs” of Nairobi and is home to an abundant collection of flora and fauna. But what made the experience more interesting for me was learning about its tumultuous past.

Karura Forest once experienced crime, land grabbing, and violence. On January 8, 1999, Wangari Maathai, Nobel Peace Prize laureate, and her cohorts were beaten by armed guards for demanding government accountability and protesting harmful state-sanctioned activities in the protected land. The attack was met with international outrage and soon after, widespread protests ensued.

Today, the forest remains to be one the largest of only three main gazetted forests in Nairobi and serves as a lifeline of the city’s biodiversity. It employs hundreds of people, houses thousands of tourists, and continues to promote inclusive indigenous practices on conservation and environmental protection. It is unfortunate, however, that the majestic forest is not immune to the jarring impact of climate change as manifested in the drought experienced by the once-alive Lily Lake.

When I asked Ruth Aura, a Mombasa-based journalist, what the world can learn from Kenya and its treatment of Karura Forest, she answered, “We’re not perfect, but we’re trying. As journalists, we must make sure that indigenous peoples are always included in these discussions since they are the ones who are heavily affected by environmental matters. I think that’s what the world can learn from us.”

(Un)muted voices

In one of the sessions, we had an activity where two photos were flashed on the screen. The task was for us to identify which photo “looked” indigenous.

At first, I felt a little bit uncomfortable because, whether I admitted it or not, my mind instinctively selected the photo that conformed with how the media often portrays what an indigenous person is supposed to look like. But deep inside, I was deliberately trying to shed that internal bias because IPs aren’t limited to arbitrary notions of what is indigenous-passing or not. They come in all shapes and sizes.

So, I answered “neither.” I was wrong.

The task was a lesson on perception, and according to Stella Paul, an international multimedia journalist, “perception does not always have to be the truth.”

This is where journalists come into the picture—to go further and beyond.

In every journalism workshop that I have attended, there is one famous quote that has always been cited repeatedly by speakers, albeit in different variations: “If someone says it’s raining, and another person says it’s dry, it’s not your job to quote them both. Your job is to look out the window and find out which is true.”

As journalists, our work is anchored on facts, especially at a time of massive disinformation in public and digital spaces. However, in those moments of finding out whether it is indeed raining or not, let us be reminded that our role as journalists is to amplify the voices of those we claim to serve. We are not the voice of the voiceless nor are we the representatives of disenfranchised communities because they’ve always had a voice, the problem lies within institutions that continue to shut them out of conversations in the first place.

It’s about time we listened.

Onward, upward

While it can be argued that many of the things we learned could have been done online, with the increasing presence of webinars and Zoom-based workshops, I strongly believe that the screen pales in comparison to the actual feeling of being immersed with people whose stories and experiences transcend language and distance. From learning Fijian phrases to tasting Nepali snacks, to bargaining for cheap prices at the Maasai Market, the three-day workshop proved to be more than just a classroom-based learning experience.

But one of the greatest takeaways from my short stay in Nairobi is that the future of indigenous environmental journalism is bright. As I go back to the Philippines, it brings me comfort to know that while a handful of challenges make reporting fact-based information a difficult task, there are young, smart, and ambitious journalists from around the world who continue to hold the line.

This story was produced with support from Internews’ Earth Journalism Network.

(Paul Mart Jeyand J. Matangcas is a freelance journalist interested in reporting about the environment, migration, and indigenous narratives. You may reach him at pmjjmatangcas@gmail.com.)