BOOK REVIEW

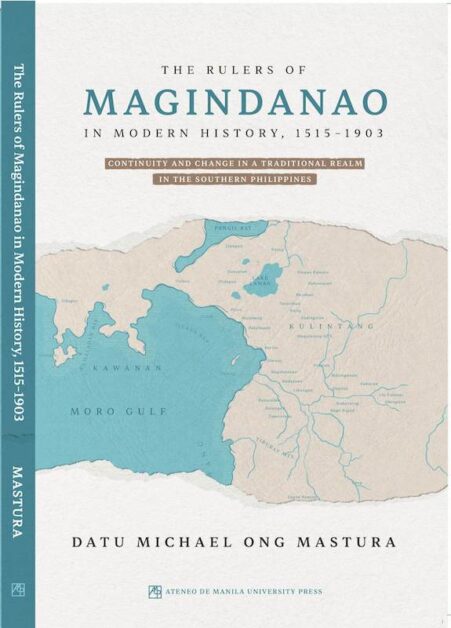

THE RULERS OF MAGINDANAO IN MODERN HISTORY, 1515-1903

(Continuity and Change in a Traditional Realm in the Southern Philippines)Author: Datu Michael Ong Mastura

Published by the Ateneo de Manila University Press, 2023

CEBU CITY (MindaNews / 25 April) — Centuries before “civilized” Europe – especially Portugal and Spain, and later on the Netherlands and United Kingdom – “discovered” the countries of Southeast Asia, there were already thriving kingdoms in Southeast Asia – including Mindanao – with high levels of social organization and governance.

Centuries before the setting up of the Republic of the Philippines in 1898 (but which soon after was abolished by the American Occupation to be restored only in 1946), there was already a rising polity in the south of our archipelago constituted by a cosmopolitan society which developed political alliances.

Centuries before the country saw the emergence of urbanized areas which served as commercial and trading centers today such as Manila, Cebu and Davao, there were trading ports from Magindanao to Jolo that had established trading connections with the rest of the Southeast Asian region from Ternate to Malacca to Brunei attracting Chinese, Spanish and Dutch merchants to transact business and/or barter goods and commodities including silver and gold.

Centuries before the population of Mindanao shifted into its current demographic profile with the majority of its citizenry constituted by descendants of migrant settlers from the North (mostly Christians), Mindanao-Sulu was sparsely populated only by its original inhabitants, namely the indigenous natives (both those who remained ensconced in their indigenous cultures now popularly known as Lumad and those who embraced Islam known as Moro).

Centuries before the Bangsamoro (BARMM) territory has been reduced to a very limited area of south-western and south-central Mindanao – after the long years of violent conflict, rebellion and peace negotiations – the Sultanates of Mindanao-Sulu dominated not just most of Mindanao but were expanding into the Visayas and Luzon.

Centuries past, Mindanao-Sulu – now referred to as the backwaters of the Republic – was in fact the territory considered “the center.” Pushed to the periphery with the occupation of two colonial masters and the eventual Manila-centered Republic, the writing of the country’s history would eventually focus on events happening in the North. Filipino historians – schooled abroad or in Manila – hardly dealt lengthily with the historical events in southern Philippines. What was more highlighted mainly were the colonization processes that led to the anti-Spanish/American armed struggles taking place mainly in Luzon and the birth of the north-dominated Republic.

This is why, in spite of these significant background historical narratives, most Filipino pupils and students – when taught about the history of their country – are hardly provided such information for them to appreciate that Mindanao was the earlier site of the local people’s brave attempt to set up Sultanates that corresponded to the Kingdoms across Southeast Asia. And that long before the colonial masters aimed to subjugate the Moro people, for centuries they already proved capable of ruling their own territories and advancing in the art of governance.

It is only because of recent initiatives of local Mindanao historians that slowly there have been published historical accounts of the significant events in Mindanao-Sulu. And exemplary publication has been the efforts of the History professors of the various branches of the Mindanao State University (MSU) – led by Dr. Juvanni Caballero – to produce a textbook that focuses on the history of Mindanao-Sulu-Palawan. At least students reached by the MSUs have a little bit more information regarding the Minsupala region to supplement the history books of Agoncillo, Constantino, Ileto et al.

It was not because of the lack of published books and available archival documents and materials – which can now be easily accessed. In fact, if one has the patience to look at Bibliographies that list all historical accounts written by Spanish and Dutch chroniclers, American historians and anthropologists and those written by both foreigners and Filipino authors in the contemporary period, one is surprised at the long list of both published and unpublished documents on the various aspects covering what we would refer today as Mindanao-Sulu Studies.

Students who are now attuned to decolonial and post-colonial theories might claim that the mostly available literature written by non-Filipinos (traversing the periods when Spanish, Dutch and American writers monopolized all written accounts) have a colonial bias and have only manifested their bias against our ancestors who they considered “wild, uncivilized, primitive, ruthless,” etc.). While this might be true, nonetheless these are important documents for these are the only ones available for researchers today to have a glimpse of what were the realities then. However, there is now a book they can read from a decolonial perspective, by someone who comes out of the periphery claiming its place in the center of Philippine historical discourse.

And now comes Datu Michael Ong Mastura’s THE RULERS OF MAGINDANAO IN MODERN HISTORY, 1515-1903 (Continuity and Change in a Traditional Realm in the Southern Philippines), published by the ADMU Press which was just recently launched in Cotabato City.

(The book will be launched at the Ateneo de Manila University on Thursday afternoon, May 4, 2023, with a lecture by the author)

If there is any book out there that Filipinos – and not just the Moro people of this Republic – should read so they can claim to really know their country’s inclusive history, it is Mastura’s masterpiece of historical writing!

The thick book (409 pages) has nine Chapters: 1) The Problem of Reconstruction in Magindanao History, 2) The Magindanao Dynasty and the Dumatus, 3) The Rajah Buayan in Buayan and the Rajahs of Sa-raya, 4) The Asala of the Datus of Mindanao, 5) Polarization under the Treaty Relations, 6) Mandawi Dar-ul Salam Indigenous Political System, 7) The Establishment of the Politico-Military Government of Mindanao, 8) Conditions in Moroland on the Eve of the 1896 Revolution and 9) Reappraisal and Epilogue

This book is the product of the author’s life commitment to document and write about his descendants. Rooted within the memory of his being a direct descendant of Sultan Muhammad Dipatwan Qudarat of the Magindanao Sultanate (whose reign took place in 1619-1670) – perhaps the most known Sultan ever to appear in Moroland’s historical narrative – Mastura took pains to dig into all available records and archival documents in libraries and data bank from Cotabato to Manila to Singapore to London to Washington D.C,, read through the long list of background literature and secured oral histories by interviewing key informants.

Included in this long list of resource materials are indigenous sources (including mythical stories inserted into genealogical accounts), manuscripts and original works in Spanish, collection of documents and papers, books and other sources and additional references. Which is why the author began working on this manuscript since the 1970s to finally be published only in 2023. If you are covering a period of 388 years of historical developments and making sure of the accuracy of data integrated into the text, an author certainly needs almost half-of his lifetime to finish this gargantuan project.

The main indigenous source are the Magindanao, Rajah Buayan and Iranun tarsilas which are kept intact in the collection of the author and Datu Kali Maulana Adax, supplemented by Najeeb Saleeby’s translation into English of Studies in Moro History, Law and Religion. A tarsila according to Saleeby is a genealogical account that provides “’a succinct analysis of the tribes or elements’ of the Muslim Filipino society and is ‘the most reliable record of historical events in the island,’ even antedating Islam.” The author also referred to the books written by Dr. Cesar Majul and Fr. Horacio dela Costa SJ as supplemental source of information.

The available tarsilas that have survived this long historical period goes back to the arrival of Shariff Kabungsuwan who began to rule since 1515 after he arrived in this location from Johore, following the years when the Portuguese – taking over the thriving port of Malacca – forced them out to migrate to the southern end of the Malay peninsula. He brought along Islam as well as the sultanate form of governance. It was from Kabungsuwan that the three royal houses of the Pulangi valley claimed punitive lineage. The legendary Tabunaway (of the mythical story involving Mamalu) was then the ruler of this locality but later sovereignty was passed over from him to Kabungsuwan.

While this book is classified under the field of History as well as Politics and Government, its contents cover other fields of inquiry especially anthropology. Educated and trained as a lawyer, Mastura branched into other fields of study in order to write this book. In the process, The Rulers of Magindanao, is a product of a multi-disciplinary scholarship. For as Jo Guldi and David Armitage posit: “By combining the procedures and aspirations of both the humanities and the social sciences, history has a special (if not unique) claim to be a critical human science: not just as a collection of narratives or a source of affirmation for the present, but a tool of reform and a means of shaping alternative futures.”

In the original Preface of this book written in 1979 (a second one was written forty-two years later in 2021), the author states why he wrote this book: “(T)he conviction that traditional social structure in Mindanao has received little attention from professional and observer-writers impelled me to do the work. Since childhood, my own exposure as the object of historical distortions and societal change in our ruling family traditions has been tremendous…To appreciate the transformation from the old order, one cannot avoid noting the geographic setting and its subdivisions, the conflict patterns, the economic stagnation, and at times the violent responses marking the mark of events…In addition… I have also attempted to give a fragmentary sketch of the cultural and social kinship system of Magindanao, Buayan and Kabuntulan.”

If one looks at the map of the Cotabato region, one can readily see the interfacing of these three localities to the Pulangi River which figures prominently in this historical narrative. One can also understand why Kabungsuwan established in this area the royal houses of Magindanao and Buayan. When he reached this location, Kabungsuwan anchored at Tinundan, an estuary close to the mouth of the Pulangi River which extended to a valley also referred to as Rio Grande de Mindanao. This valley was ideal to be a homeland as it extended from the foothills of the Tiruray ranges to the Ghores of the sea. With this major river flowing across a vast territory, it served as the main channel of communications.

As the Magindanao and Buayan sultanates progressed to a high level of governance, they expanded their dominant presence covering an extensive area including the Davao region even up to Agusan-Surigao in the east, to what is now parts of Zamboanga del Sur located along the coast of Moro Gulf in the west as well as Bukidnon and Lanao in southcentral part of the main island. The sultans and their descendants intermarried with the Iranuns, the Taosugs and indigenous peoples like the Blaans thus expanding the royal lineage to other ethnicities.

Trading links reached Manila up in the north and most of the trading ports in the Malay peninsula.

The most known of the long list of Sultans is Qudarat whose lineage goes back to Kabungsuwan. The son of Kapitan Laut Buisan who ruled from 1597, Qudarat’s reign was from1619 to 1671 and he died at age ninety. He was actually the first to be invested with the Sultan’s real powers and thus represented the ruling hierarchy, hinting that this had led to the development of a “feudal kingship…(thus) “becoming the only Moro ruler to define his dominion against the claims of the European colonial powers.”

Alternating between seeking treaties with the Spanish and Dutch colonizers (in 1645 he signed a treaty negotiated by Alejandro Lopez that defined the territorial boundaries between his Sultanate and the Spanish colony) as well as fighting wars with them while mobilizing Caragans, Maranaos and natives of Butuan and Dapitan to be his foot soldiers. He even fought with Sultan Kandahar of Sangir Island in order to annex Sarangani Island to his territorial domain.

As the Spanish colonial regime sought to overpower the Sultanates – which led to some of the most violent Moro Wars – 18 treaties were signed by the Sultans and Spanish Governor-Generals or their envoys between 1605 to 1888, mostly aimed at “cessation of hostilities, recognition of the political integrity of the Sultanate and its territorial domains, defining territorial boundaries, setting up defensive-offensive alliance, establishment of trading post, setting up provisions binding the sultan not to make contracts nor new agreements with other foreign powers, allowing a Spanish trading post in Cotabato and the one in 1888 where Rajah Putri and Datu Utu agreed to an act of conciliation with the Spanish sovereign King Alfonso XIII and respecting the religion of Islam and the customs of the royal family.

The last name that appears in the book’s list of Sultan is that of Mangigin, son of Datu Dakula of Sibugay in 1896. But by 1899 “all Moro traditional authority in the Pulangi had been enfeebled; every strong member of the aristocracy had been crushed or passed away,” thus signaling the collapse of the Sultanate. In the interval between the Spanish evacuation and the encroachment of the Americans, the combined leadership of Datu Ali and Datu Piang would attempt to recoup the supremacy of Buayan. “Datu Ali could have easily gained complete control of all territory known as the District of Cotabato…as he was the real power of the valley and 70 percent of the population were his followers.”

But as traditional authority had collapsed, the Americans concluded that Sultan Mangigin was no longer considered by Mindanao Moros as their suzerain to whom they owed no allegiance. Governor General F.B. Harrison wrote: “the Sultan of Magindanao has surrendered all pretensions of leadership…and when he dies, there will die with him a dynasty of six hundred years of power.”

The last segment of this book covers the seven-year period which chronicles the tail-end of the Spanish regime in 1896 to the setting up of the Moro Province by the American colonial government in 1903. The Spanish colonial control of the islands collapsed with the victory of the Katipunan-led Revolution in 1896 leading to the setting up of the Republic of the Philippines headed by Emilio Aguinaldo which aimed to establish its foothold over the claimed territory from the North down to the South.

An attempt was made to include representations from the Moroland. At the Malolos Congress, there were representatives from “Zamboanga, Cotabato, Davao, Basilan, Palawan, Lebak, Mati, Malabang, Tucuran, Baras and Jolo and its adjacent islands of Siassi, Tataan and Bongao…which representation was probably based on the Spanish established positions or outposts throughout the South; (who) were in large part residents of Manila.”

The Republic was doomed to last only for a very short time, as the two colonial masters signed the Treaty of Paris in 1898. The remnants of the revolutionary forces valiantly fought in the Filipino-American war that followed the Republic’s annexation to the USA. However, with more superior forces and weapons, the Americans subjugated the revolutionaries and consolidated its colonial rule. In setting up the Moro Province, the remnants of the Sultanates further disintegrated with the abrogation of the Bates Treaty and the implantation of the Civil Government. This compelled the “governors and municipal presidents…to deal directly with the people instead of with ‘the datus, sultans, leaders or caciques.” Eventually when Manuel Quezon became President, his non-recognition of the various titles further eroded the once powerful authority of the Sultanates.

In the end what could be the lessons of this historical narrative? The author provides the answer at the end of his book: “The story of the Magindanao polity’s constitution and diffusion marks the common historical process by which Asian societies in the past became an easy prey of Western colonialism. But at the same time, it provides another instance for Asian societies that have survived the strains of culture encounter and the economic forces thrust on the native fabric by social change.”

It is not only the Moro people of Mindanao who owe Datu Mastura a huge debt of gratitude for having put together this remarkable book which can easily be considered outstanding in its level of scholarship, its treatment of “space,” in combining “the study of the particular, the specific, and the unique with the desire to find patterns, structures, and regularities,” and thus asserting that henceforth Philippine history must integrate the voices that once were considered peripheral.

All citizens of this Republic should be grateful to have a publication that allows them a glimpse of the archipelago’s past.

Mastura’s book impressively follows the path of Fernand Braudel’s longue duree, “an approach to history writing pioneered by historians of the Annales school…(which)…focusses on events that occur nearly imperceptibly over a long period of time, on slowly changing relationships between people and the world.” It is a way of writing history which finds the relationship between agency and environment. For as Winston Churchill commented: “The longer you can look back the further you can look forward.”

As Mindanawon literature is expanding exponentially with a greater interest of scholars to pursue Mindanao studies, we hope more students of the social sciences will follow the path paved by Datu Mastura. We now have this exemplary work profiling the Magindanaons. We can only hope that the other ethnicities with their own social institutions and governance systems going back to the pre-colonial period will be chronicled by other scholars especially those that interfaced with the Magindanaons, especially the Iranuns, the Tedurays, the Arumanen Manuvus and the Kalagans. Their voices, too, need to be heard. Their narratives, too, deserve a place in the annals of Philippine historical accounts.

We must all find a way to participate in writing our people’s history because it is only by looking into the past that we can hope to have a better understanding of the future!

(MindaViews is the opinion section of MindaNews. Redemptorist Brother Karl Gaspar is Mindanao’s most prolific book author. Gaspar is also a Datu Bago 2018 awardee, the highest honor the Davao City government bestows on its constituents. He is presently based in Cebu City).