ALABEL, Sarangani (MindaNews / 15 August) – On May 2 this year, at the height of the lockdown triggered by the coronavirus disease (COVID-19), a large pawikan (sea turtle) appeared at the doorstep of a cottage in a beach resort in Glan town, touted as the “Boracay of the South” due to its white sand shoreline.

Emerging from Sarangani Bay, the olive ridley found her way to the Kingkim Beach Resort to hatch eggs, undisturbed as the resort was closed to the public. It was a Saturday, and if it were not for the lockdown, the secluded resort would have been brimming with the weekend tourist crowd.

A mature sea turtle photographed swimming at the Sarangani Bay. Photo courtesy of Sarangani Bay Protected Seascape

A mature sea turtle photographed swimming at the Sarangani Bay. Photo courtesy of Sarangani Bay Protected Seascape

Three weeks later, on May 27, another olive ridley nested also at the same resort located in Barangay Burias, when no tourists were around to swim in its turquoise waters or simply idle on its sandy white shore, again because of the lockdown.

“The sea turtles consider our coastal village their home apparently because they feel safe here and won’t be hurt,” Bazaron Kingkim, the resort’s manager, told MindaNews.

Beach resorts in Sarangani were closed from mid-March to May 31 to help prevent the spread of COVID-19 in the province. Starting June 1, the municipal government of Glan initially opened its beaches to residents of Sarangani and General Santos City only, with the local tourists required to book first at the resorts and present medical certificates upon entering the town.

The eggs of the first nesting olive ridley successfully hatched on June 27, with the locals releasing 46 hatchlings to the bay. It usually takes 45 to 60 days for the sea turtle eggs to hatch.

Protected seascape

Sarangani Bay has long been known for its rich biodiversity, harboring a wide variety of ecosystems ranging from mangroves, seagrasses and the varying depths of coral reefs. Some parts of the bay have been described as world-class diving spots.

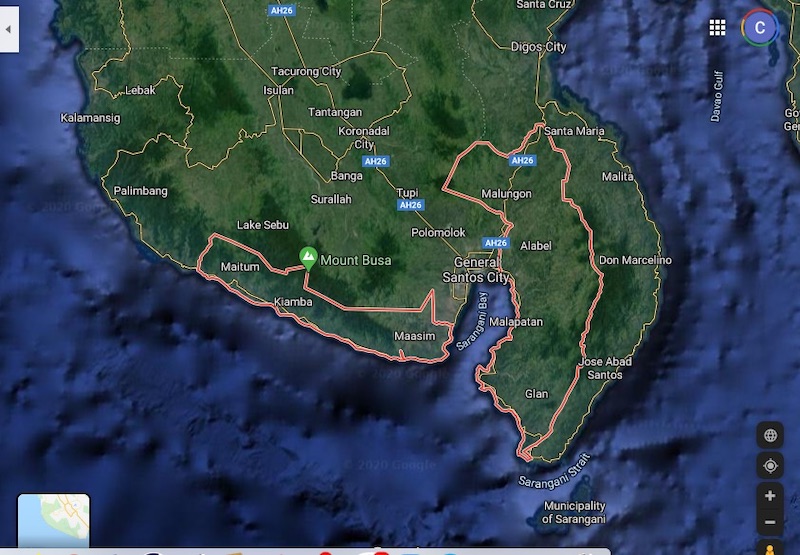

In 1996, then President Fidel Ramos issued Proclamation 756 establishing the Sarangani Bay Protected Seascape (SBPS), covering 215,950 hectares across the towns of Glan, Malapatan, Alabel (the provincial capital), Maasim, Kiamba and Maitum, and the chartered city of General Santos.

Sarangani province and bay. Courtesy of Google Maps

Sarangani province and bay. Courtesy of Google Maps

The SBPS is home to some threatened species such as dugong (sea cow), mameng (Napoleon wrasse), and four kinds of marine turtles (hawksbill, olive ridley, loggerhead and green sea turtle). Across the bay, at least 411 reef species have flourished.

Other notable fauna found in Sarangani Bay are dolphins, whales, sun fish, giant clams and shore birds. There are at least 27 mangrove species dominated by pagatpat (Sonneratiaceae), bungalon (Aviceniaceae) and bakawan (Rhizophoraceae) and at least 11 species of seagrasses.

Thousands of families depend on their livelihood on Sarangani Bay, where pelagic species such as bilong-bilong (Mene maculata), tulay or matambaka (Selar crumenophthalmus), bolinao (Encrasicholina punctifer), bangsi (Cypselurus opisthopus), sambagon (Katsuwonus pelamis), are aplenty.

Bane and boon

Sarangani has been on extended modified general quarantine since June 1.

For majority of Filipinos, the lockdown triggered by COVID-19 was a bane especially with the restriction of movement and the shutting down of office and business operations that affected tens of thousands of workers nationwide.

File photo of the sea turtle hatchery in Maasim, Sarangani. MindaNews photo by BONG S. SARMIENTO

File photo of the sea turtle hatchery in Maasim, Sarangani. MindaNews photo by BONG S. SARMIENTO

On August 6, the Philippine Statistics Authority revealed the country crashed into a recession as the economy shrank a record 16.5 percent during the second quarter.

President Rodrigo Duterte in mid-March ordered the lockdown in the National Capital Region, home to some 12 million people, to fight the virus, a move which local government units in the rest of the country eventually followed.

For Sarangani, its first confirmed COVID-19 case was recorded on May 18 and the second at the end of that month. With the easing of the lockdown in June that allowed locally stranded individuals and returning overseas Filipinos to go home to their provinces, the COVID-19 cases in Sarangani surged.

As of 6 p.m. on August 15, Sarangani recorded 72 COVID-19 cases, out of which 54 have recovered while 18 are still considered “active cases,” according to the Department of Health’s Center for Health Development in Region 12 (Soccsksargen).

But while COVID-19 clearly was a bane to humankind, it was a boon for marine biodiversity in Sarangani Bay.

Nesting haven

Sitting in her office in Alabel town with a large television screen showing the amazing underwater world with schools of fish swimming in corals, Joy Ologuin, SBPS superintendent, stressed the need to protect Sarangani Bay even more after the lockdown restrictions have been eased.

“The COVID-19 lockdown last March (to end of May) prevented tourists from going to our beaches. But it allowed the marine biodiversity to breathe and rest, especially the sea turtles that made a notable return to Glan and other parts of Sarangani province,” she told MindaNews.

Joy Ologuin, Sarangani Bay Protected Seascape superintendent, at her office in Alabel, Sarangani. MindaNews photo by BONG S. SARMIENTO

Joy Ologuin, Sarangani Bay Protected Seascape superintendent, at her office in Alabel, Sarangani. MindaNews photo by BONG S. SARMIENTO

For years, the towns of Maitum and Maasim have been the more popular nesting sites for endangered and threatened sea turtles. In fact, the two towns are home to government-funded pawikan hatcheries and learning sites

During the lockdown from mid-March to May 31, at least 8,751 hatchings were released to Sarangani Bay from the different parts of the province, according to SBPS data.

Majority of the sea turtle hatchlings remained in Maitum and Maasim towns but many were also recorded in Glan, Alabel and even Malapatan.

About a dozen hatchings were noted in Glan, five in Alabel and two in Malapatan.

For that same period SBPS logged over at least 100 hatchings in the adjoining towns of Maitum and Maasim.

For decades, Sarangani’s shores have hosted the nesting of olive ridley, hawksbill, green sea and loggerhead sea turtles.

Olive ridley is the most common species found in the area.

Also known as Pacific ridley, olive ridley (Lepidochelys olivacea) is categorized as vulnerable, meaning its population is decreasing, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species.

The IUCN has also classified Hawksbill (Eretmochelys imbricate) as critically endangered, green sea (Chelonia mydas) as endangered and loggerhead (Caretta caretta) as vulnerable.

“Most of the time, humans are the problem”

Reiterating that the COVID-19 lockdown reduced the stress and pressure on Sarangani Bay, Ologuin cited the need to continue the conservation awareness campaign in communities along the bay to conserve the sea turtles and other aquatic resources.

“Compared to a few years ago, the awareness on sea turtle conservation by residents in coastal communities has become better. It must be sustained,” she said.

Sea turtle hatchlings released to the Sarangani Bay. Photo courtesy of Sarangani Bay Protected Seascape

Sea turtle hatchlings released to the Sarangani Bay. Photo courtesy of Sarangani Bay Protected Seascape

Republic Act 9147 or the Wildlife Resources Conservation and Protection Act passed in 2001 punishes persons who, “willfully and knowingly exploit wildlife resources and their habitat” or kill and destroy wildlife species unless for allowed instances; collect, hunt, possess, trade wildlife and commit other acts the law enumerated as illegal.

The law imposes a jail term of six to 12 years and fines ranging from 100,000 to one million pesos for persons who undertake illegal acts against species listed as critical; four to six years imprisonment and a fine from 50,000 to 500,000 pesos if inflicted against endangered species; and two to four years imprisonment and a fine of 30,000 to 300,000 pesos if inflicted against vulnerable species.

In a study entitled “Environmental Issues and Mechanisms in Protecting Marine Turtle Nests in Maitum, Sarangani,” Nannette Nacional, Maitum town’s environment officer, stressed that sea turtles play a big role in the marine ecosystem, hence they need to be conserved and protected.

The study, submitted in June 2020 to the graduate faculty of the Mindanao State University in General Santos City, was part of Nacional’s requirements for her Masters in Sustainable Development Studies Major in Community Development.

“Most of the time, humans are the problem,” she said, referring to why sea turtles have either become endangered or threatened.

Despite the hefty fines and jail term for violators as well as awareness campaign, Nacional said some residents in town continue to hunt marine turtles and their eggs for consumption or business purposes.

She recommended, among others, the need to strengthen the enforcement capacity of the local government’s Bantay Dagat (Sea Watchers) and the prosecution of offenders.

“Sea turtles are worth saving. They are part of beaches and marine systems, which are essential ecosystems. If they go extinct, such essential ecosystems will deteriorate,” Nacional stressed.

Ologuin said they have been regularly monitoring the bay’s health, in partnership with other national government agencies and the local government units straddled by Sarangani Bay.

Sarangani Bay is still healthy

“The presence of sea turtles and other marine mammals within Sarangani Bay manifests that the bay is still healthy,” she said.

Based on the regular monitoring from last year up to July 2020, Gary John Cabinta, ecosystems management specialist of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources’ Provincial Environment and Natural Resources Office-Sarangani, said they recorded the presence of 40 to 60 spinner dolphins (Stennella longirostris) in Malapatan and Glan towns, 150 to 200 fraser’s dolphins (Lagenodelphis hosei) in General Santos City and Glan, four pygmy killer whales (Feresa attenuate) in Malapatan and Glan, 16 risso’s dolphins (Grampus griseus) in Malapatan, and two dwarf/pygmy sperm whales (Kogia sp.) in Malapatan.

Children release sea turtle hatchlings in Maitum, Sarangani. MindaNews photo by BONG S. SARMIENTO

Children release sea turtle hatchlings in Maitum, Sarangani. MindaNews photo by BONG S. SARMIENTO

The sightings of these marine mammals were on top of the pawikans that thrived or hatched across the SBPS, he said.

“Marine mammals can be used as indicators of the health of marine ecosystems… The presence of these marine mammals maintains the balance of the ecosystem,” Cabinta said in a report.

Sadly, garbage, including non-biodegradables, continues to find their way into the bay.

Last month, the monitoring team documented a large patch of debris consisting of plastic bottles and wrappers, diapers, sacks, cellophanes and coconut husks floating at the heart of Sarangani Bay, Cabinta said.

Since the marine debris poses great threats to the environment, especially to the marine mammals and other organisms, the local government unit of each coastal barangays must strengthen the implementation of their solid waste management systems to help regulate the trash from entering the bay, he added.

According to the DENR-Soccsksargen, there had been documented stranding and deaths of sea turtles and other marine species in the Sarangani Bay due to ingestion of plastic waste.

Cabinta also stressed the need to conduct a series of education awareness in coastal communities for the protection of the marine environment as well as regular clean-up across Sarangani Bay to lessen the threats of plastics ingestion among large marine organisms.

For Kingkim, the resort manager in Glan town, proper awareness is crucial in keeping the sea turtles from extinction.

“They will keep coming back if they feel they are not in danger,” he stressed.

Kingkim, whose resort sits next to a mosque, recalled that in his younger years, older folk in their community would perform a sumbali in order to slaughter the pawikan in conformity with Islamic rites.

“That was a long time ago. Most of us in the village now are largely aware about the need to protect the sea turtles,” he said.

(Bong S. Sarmiento of Koronadal City is Vice Chair of the Mindanao Institute of Journalism, which runs MindaNews. The production of this special report was made possible with support from Internews’ Earth Journalism Network)