MALAPATAN, Sarangani (MindaNews / 04 September) — Lumads or indigenous peoples (IPs) in far-flung or last mile communities of this quaint town need to cross the river 12 times and walk for one or two days in order to reach the población.

A first-class municipality with a population of a little over 80,000, this sleepy town has long coastlines and rolling mountains planted with coconut and corn. It is inhabited by Muslims, Christians and IPs belonging to the Blaan tribe, with the latter mostly residing in geographically isolated and disadvantaged areas (GIDA).

If it were not a death or life situation, majority of the Blaans would not go down to seek medication in the lowlands not just because of the arduous trek but also because of lack of money for transportation and for a private doctor’s fee.

It is this utter poverty of the Blaans that prompted Dr. Roel Cagape to conduct free medical missions in remote Blaan communities in the mountains, where tuberculosis (TB) is among the common diseases.

Poverty is cited as among the reasons why a number of Blaans from last mile communities don’t get to complete the six-month TB treatment. MindaNews photo by BONG S. SARMIENTO

Poverty is cited as among the reasons why a number of Blaans from last mile communities don’t get to complete the six-month TB treatment. MindaNews photo by BONG S. SARMIENTO

TB, a preventable and curable disease, is the leading infectious disease killer and one of the top ten causes of deaths globally. The Department of Health’s National Report 2020 noted that three Filipinos die of TB every hour.

“I’ve encountered many TB cases in the mountains among the Blaans who can’t even have a sputum (phlegm) test because of the exorbitant motorcycle fare to the lowland, besides the one or two days for walking in the jungles and crossing rivers,” Cagape, who specializes in family medicine, told MindaNews.

Fare for the motorcycle ride, commonly referred to as ‘habal-habal,’ costs 600 pesos per person.

Dr. Roel Cagape, MD, founder of Hearts and Brains, Inc., checks his phone at his clinic in Malapatan, Sarangani province. MindaNews photo by BONG S. SARMIENTO

Dr. Roel Cagape, MD, founder of Hearts and Brains, Inc., checks his phone at his clinic in Malapatan, Sarangani province. MindaNews photo by BONG S. SARMIENTO

Cagape, a native of this town, lamented that many of the TB patients he would refer to the Rural Health Unit (RHU) for treatment would discontinue their medication due to their distance from the town proper.

TB treatment entails at least six months but the RHU does not give all the medicines to a TB patient in one handout.

The patient, or an authorized representative, needs to come back weekly at the health center to replenish the drugs to cure TB, which many from the tribe cannot comply with because of the transportation expenses, he said.

Depending on the local government units, medicine replenishment could be weekly or monthly. The Department of Health’s (DOH) policy is to give the TB patient a maximum supply of medicines good for one month.

Fare more expensive than treatment cost

Nine of the 12 barangays in Malapatan are classified as GIDA or last mile communities, including the village of Kinam, where one-way motorcycle fare is 600 pesos per person. That would be 1,200 pesos for one trip alone for an unaccompanied patient per week. A four-week period means one has to shell out 4,800 pesos to get the free anti-TB medicines or 28,800 pesos for six months to complete the treatment.

A six-month TB treatment, including the medicines and the laboratory tests, costs around P4,000.

Habal-habal (passenger motorcycle) drivers maneuver a dirt road in a Blaan community within Barangay Poblacion, Malapatan, Sarangani. MindaNews photo by BONG S. SARMIENTO

Habal-habal (passenger motorcycle) drivers maneuver a dirt road in a Blaan community within Barangay Poblacion, Malapatan, Sarangani. MindaNews photo by BONG S. SARMIENTO

“That’s beyond the spending capability of many Blaan families in the mountains,” said Cagape, noting they would rather spend their meager cash to buy food than spend it for their health needs.

Jenelyn Yaton, a Blaan barangay health worker, noted the lack of professional health workers in the town who can tend to the needs of constituents in far-flung villages in the area.

“Kulang ang health workers, wa sila gatungha sa bukid…Luoy kaayo ang tribu (There’s a dearth of health workers, you seldom see them in the mountains. The tribe is pitiful),” she told MindaNews.

Her uncle contracted TB about three years ago, and managed to get cured after six months of uninterrupted medication.

That’s because her uncle and his family live closer to the town center. Although the inner stretches of the road going to Sitio Sapia in Barangay Poblacion, where they reside, is rough and difficult even for a pick-up truck to maneuver, people there can reach the town in about 30 minutes through motorcycle for P100 per person, one way.

The family was keen on ensuring the uncle gets cured so a family member religiously brings the packs of consumed medicines every week to get fresh supplies, even if it costs them money for transportation.

Yaton said 100 pesos is “a big amount for us poor tribal members. Mostly, those from far-flung communities do not bother about conventional medication because they are far and because of the fare.”

A pastor of the Amazing Grace Alliance Evangelical Church and a mother of four, Yaton noted that accessibility to the rural health center plays a huge factor in the fight to curb TB and other diseases such as malaria and diarrhea among the Blaan tribe.

Replenishing medicines

The DOH had rolled out the Tuberculosis -Directly Observed Treatment Short-Course (TB-DOTS) program as its overarching strategy to combat TB, which is caused by a bacterium called Mycobeacterium tuberculosis that mainly affects the lungs.

A person gets infected by inhaling droplets containing the bacteria.

Under TB-DOTS or “Tutok Gamutan,” patients can get the TB drugs replenishment if a trained health care worker or other designated individual (outside the family, ideally) could attest that they have taken the medicines as prescribed.

But since the town has limited health workers especially in the remote areas, Yaton said one of their kin would bring the empty packets of TB drugs as “proof that they had been taken by the patient,” so that their uncle can get fresh doses.

Her 89-year-old uncle was cured of TB three years ago. He passed away last year.

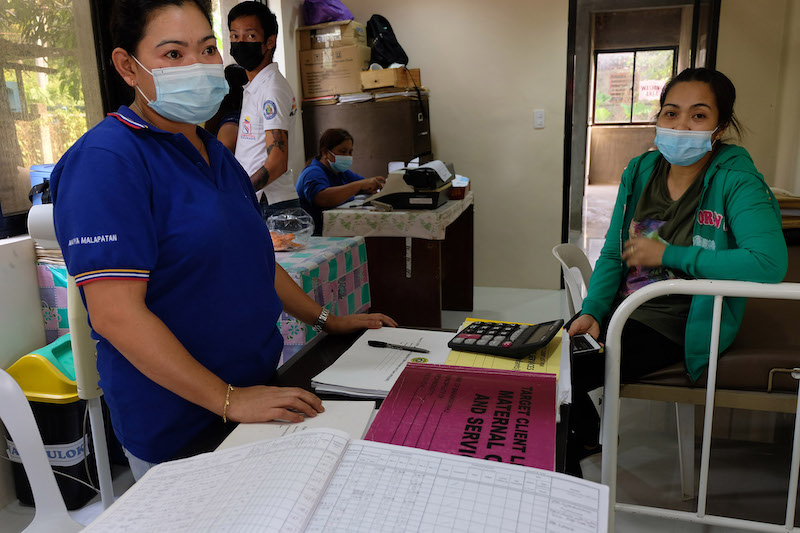

The Rural Health Unit in Barangay Poblacion, Malapatan, Sarangani hosts a TB-DOTS facility. MindaNews photo by BONG S. SARMIENTO

The Rural Health Unit in Barangay Poblacion, Malapatan, Sarangani hosts a TB-DOTS facility. MindaNews photo by BONG S. SARMIENTO

Yaton, who receives a monthly allowance of less than 2,000 pesos as a barangay nutrition scholar in charge of four scattered communities, said residents in these GIDAs are not seeking medical treatment, or discontinuing medication for long-term diseases like TB, due to lack of money for transport to the faraway rural health center.

To address the problem, Mary Grace Planas, a rural health worker here involved in the treatment of TB, said they would send a month’s supply of medication drugs for registered TB patients to a midwife assigned in the mountains.

The patients can get the TB drug supplies from their midwife, she added.

However, Dr. Cagape, who serves or examines dozens of poor patients Monday to Friday at his two clinics here free of charge, noted that such is not usually the case.

Discontinued treatment

In the remotest areas of Malapatan, residents don’t often get to see professional health workers as they are assigned few and far between the communities, said Cagape, who performs minor surgeries before the COVID-19 pandemic struck last year and gives out free medicines to patients, sourced from donations to the non-government Hearts and Brains, Inc., which he founded in 1995.

Planas confirmed what Cagape and Yaton have been saying — that there are residents who discontinued medication for TB, or are not at all seeking medical intervention for other diseases. “They’re very far away and they have no money to spare for transportation, that’s why they can’t come here to seek medical help,” she said.

The Rural Health Unit in Barangay Poblacion, Malapatan, Sarangani hosts a TB-DOTS facility. MindaNews photo by BONG S. SARMIENTO

The Rural Health Unit in Barangay Poblacion, Malapatan, Sarangani hosts a TB-DOTS facility. MindaNews photo by BONG S. SARMIENTO

If a patient fails to complete the six-month medication period for TB, the case would develop into what they dub as TB multi-drug resistant, a condition that would need longer and costly treatment of 18 to 24 months.

Cagape stressed the traditional health practices of the Lumads, including herbal medicines, can not cure TB.

“Only conventional medicines can cure TB if taken completely as prescribed,” he added, noting he usually refers TB patients to government health centers.

Cured and completed treatment

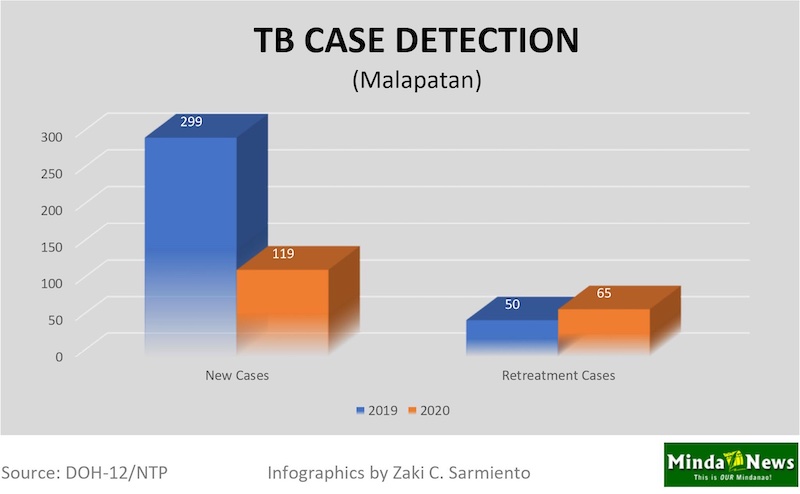

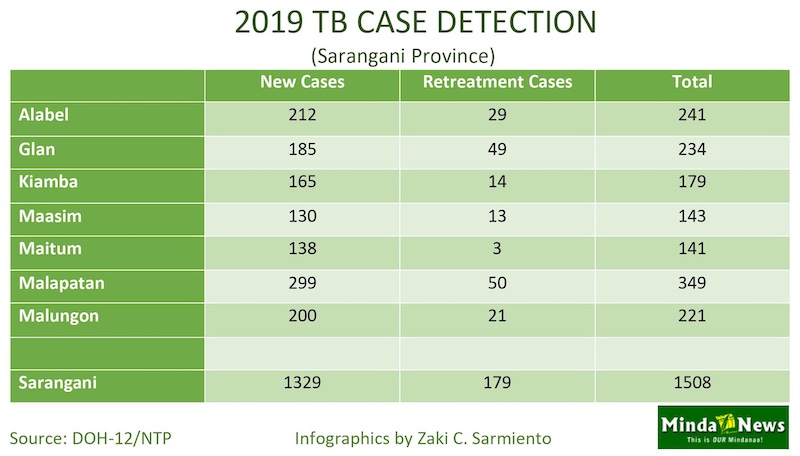

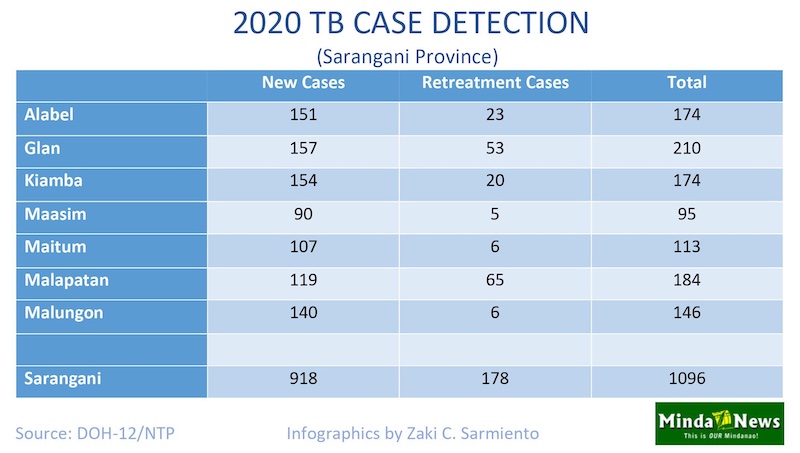

Data from the Department of Health – Region 12 (DOH-12) showed that the 2019 case detection in Malapatan town totaled 349 (299 new cases and 50 retreatment cases) and 184 (119 new cases and 65 retreatment cases) for 2020.

Retreatment cases involve a patient who had been treated for any form of TB before but has initiated treatment again following relapse or failure to complete the medication regimen.

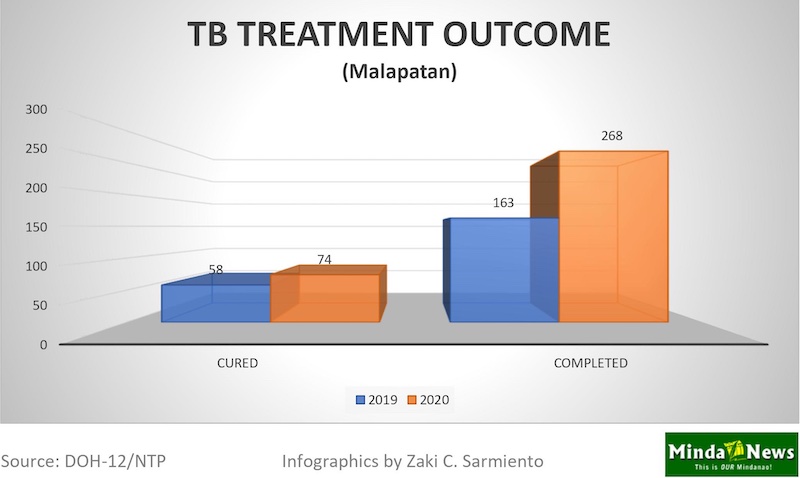

For the treatment outcome in this town, 58 persons were cured and 163 others completed treatment in 2019, for a total of 221.

For 2020, 74 persons were cured and 268 others completed treatment, for a total of 342. Two patients died from TB during the period.

“Cured” means they were proven free of TB through laboratory tests while completed treatment means they finished the six-month treatment but were not tested in the laboratory to have been free of the bacteria, according to Kamlon Usman Jr., RN, DOH-12 National TB Control Program nurse coordinator.

Sarangani recorded 1,508 TB cases in 2019 and 1,096 in 2020.

The cohorts for the 2019 and 2020 data were from their preceding years(2018 for 2019 and 2019 for 2020).

The cohorts for the 2019 and 2020 data were from their preceding years(2018 for 2019 and 2019 for 2020).

Shared responsibility

Usman stressed that the patient and the health worker both have a responsibility in treating TB.

“There are social issues attached to the treatment of TB. It does not depend only on the patient but also on the health worker,” he told MindaNews.

Usman echoed what Cagape, Yaton and Planas said, that patients from the GIDAs usually do not complete the six-month treatment due to the distance to the rural health center and lack of money for transportation to get free medicines.

Also, since the treatment takes a long time — six months of daily medication involving several drugs — they stop their medication after feeling well just a few weeks or months from the start of the treatment, he said.

Usman noted that such is part of “Filipino behavior” — discontinuing the medication if they already feel well.

“For TB, the medication must be completed in six months for the bacteria to be totally eradicated from the lungs. If you stop the medication before the prescribed duration, the bacteria will not be removed and the symptoms will recur again,” he explained.

On the part of the health workers assigned in last mile communities, Usman said they often wear several hats — as midwives and nutritionists – aside from monitoring the TB patients.

Because they are burdened by other responsibilities, that affects the fight against TB, he stressed.

“The way the health worker deals with the patient also has a bearing in the treatment outcome of TB disease involving those in the GIDA areas. For example, does the health worker religiously follow-up their patients or leave them alone after giving them the drugs?” he asked.

Since the health worker (usually a midwife) is responsible not just for one but several villages or communities, local government units like Malapatan employ the help of barangay health workers like Yaton, who get a meager monthly allowance of less than P2,000.

“The barangay health workers are the unsung heroes in our fight against TB because they are the ones mingling with the people in far-flung communities,” Usman said.

TB kills 3 Filipino every hour

Under the Sustainable Development Goals, the United Nations targets to end the TB epidemic by 2030 globally.

In 2019, the Philippines ranked fourth among the countries with the highest number of TB cases, according to the Global TB Report 2020. Topping the list was India followed by Indonesia and China. The Philippines had the highest TB incidence rate in Asia, with 554 TB cases per 100,000 people in 2019.

The DOH has declared TB a priority, rolling out the #TBFreePH campaign in a bid to encourage Filipinos to get the care they need to avoid negative health outcomes in the future.

In the Philippines, which has a population of 109 million, the DOH aims to find and treat 2.5 million Filipinos by 2022.

However, the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 sidetracked other health programs like TB care and prevention.

The number of new and relapse cases notified to the DOH had dropped by about 35 percent last year from 2019 as community quarantine measures restricted mobility and limited access to health facilities, according to the National TB Report 2020.

The report noted that three Filipinos die of TB every hour, a disease that is preventable and curable.

As of 29 August 2021, data from the National TB Control Program showed that the drug susceptible and drug resistant TB cases notified to the DOH stood at 340,524, or just about 14 percent of the 2.5 million target by 2022.

Usman encouraged TB patients to continue their treatment as prescribed because that is the only way to totally ward off the bacteria from their lungs.

Stressing that the TB medicines and laboratory screenings are all free from the government, he also encouraged the immediate family members of the TB patients to get tested because of the possibility that they may have been infected.

For the Lumads in last mile communities who can’t travel to the lowland due to the distance and lack of money for fare, they can avail of TB clinical diagnosis without having to leave their communities.

That is through the “E-text si Doc,” a free service where the public can consult their medical condition with Cagape, a multi-awarded physician whose latest distinction is the Ozanam Award given by the Jesuit-run Ateneo de Manila University to “Christians who have given distinctive and continued service to their fellowmen in accordance with the principles of justice and charity.”

Cagape also hosts a daily radio program “Sagot ka ni Doc” aired weekdays over the Diocese of Marbel-owned DXCP in nearby General Santos City, where he provides health education and offers medical advice to patients.

Cagape also hosts a daily radio program “Sagot ka ni Doc” aired weekdays over the Diocese of Marbel-owned DXCP in nearby General Santos City, where he provides health education and offers medical advice to patients.

For him, the best way to curb TB in last mile tribal communities is for the government to bring the medicines closer to the tribe, if possible door-to-door, and provide better compensation to health workers to attend to the holistic health needs of citizens in isolated and disadvantaged areas.

“Health services for TB and other diseases must be within the easy reach of the marginalized people. Health care workers should go to the communities frequently, and not the other way around involving the tribes,” he suggested. (Bong S. Sarmiento / MindaNews)

This story supports the #TBFreePH campaign of the Department of Health and was produced under the 2021 TB Media Fellowship in the Philippines. With the help of the United States Agency for International Development, #TBFreePH aims to increase and improve conversations about TB and help address stigma and discrimination experienced by persons with TB.